Reconstructing Memory

the bright blue trunk and other portals to the past

It’s funny how when you start thinking deeply about something, you suddenly see it everywhere. This is called the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon—or frequency illusion—a cognitive bias that makes new information feel omnipresent. Lately, the thing I keep noticing is memory, identity, and photography.

It’s not a new fixation. My senior thesis in college focused on how visual representations in art and media shape real-world perception. But in the past few years, it's gotten more personal.

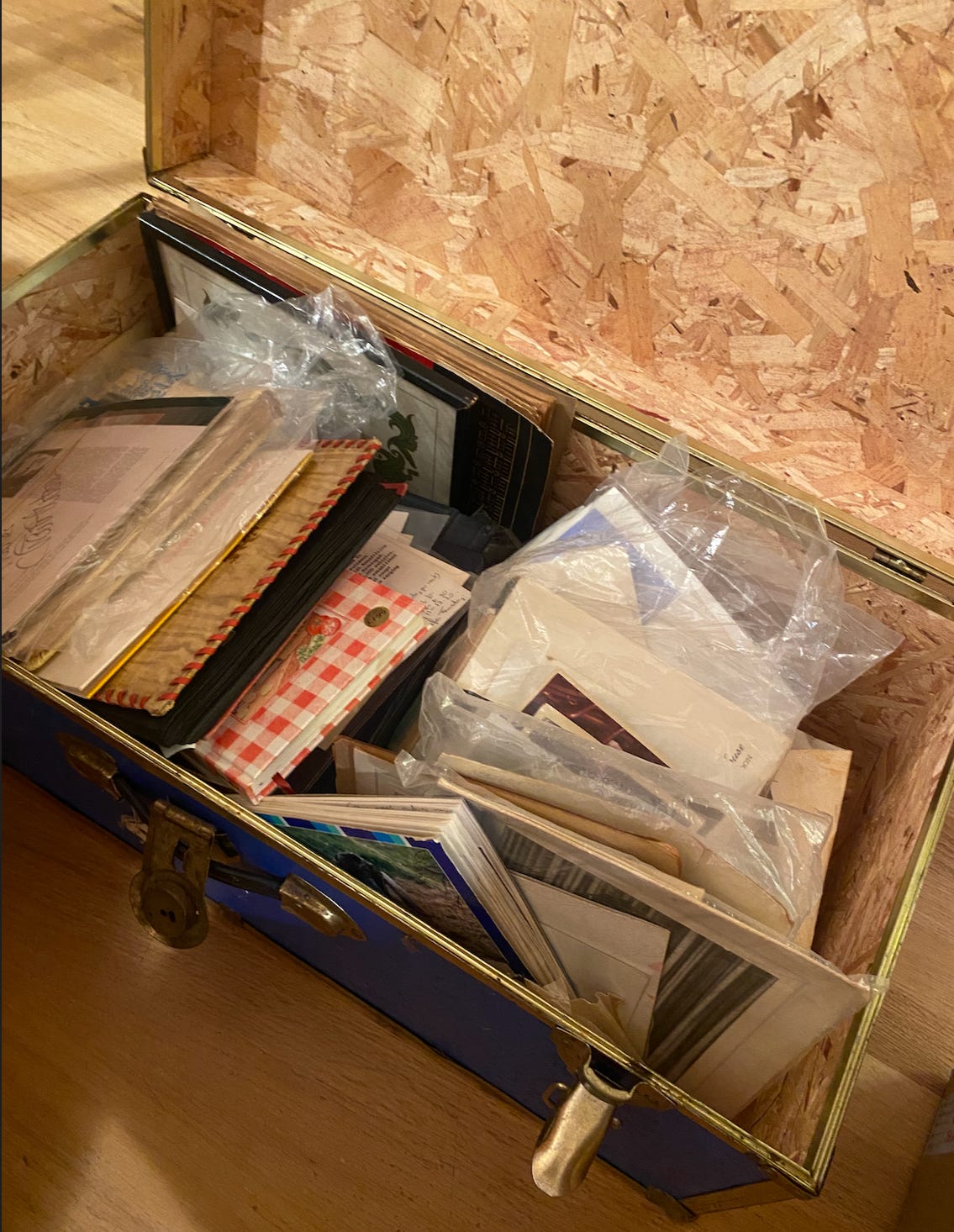

Growing up, there was always a bright blue trunk at my parents’ house, packed with my paternal grandmother’s photos, letters, and artifacts. During the early days of the pandemic, I finally started the long-conceived project of scanning and archiving it all. I've digitized hundreds of photos—but I'm still grappling with how to engage with them, how to understand them.

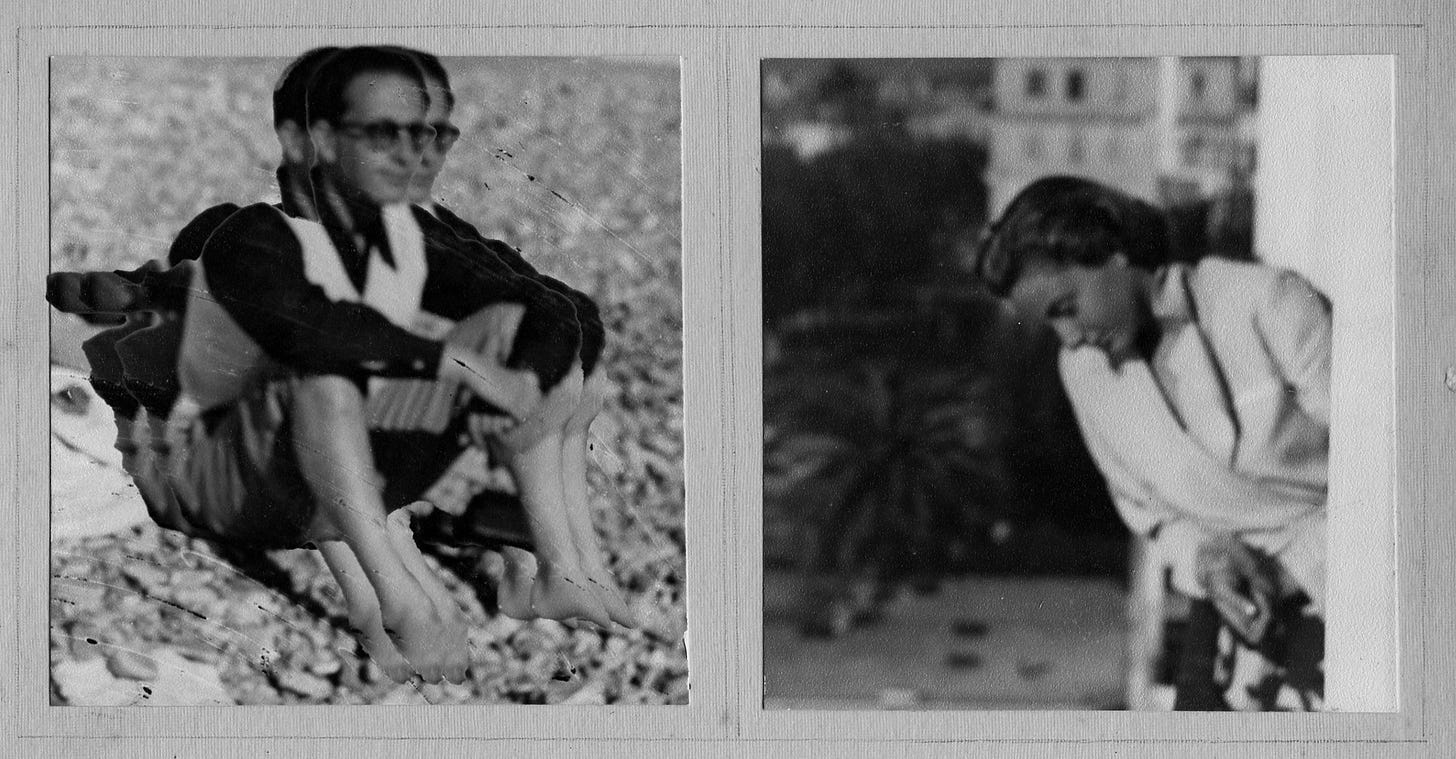

For a photo class last year, I was asked to bring in 10 images of an “abstraction of a portrait.” I manipulated photos I had scanned of my grandmother and grandfather—taken long before I was born. My grandfather died before my parents got married and his identity had always felt distant, secretive. His name was Wolfgang, and growing up he was always “the big bad Wolf” in my head. In spending hours with these images, bending and altering them, I re-entered that childhood habit of filling in the blanks, inventing stories to connect with things I didn’t fully understand.

As I sort through this family archive, I’m left with far more questions than answers. There’s something uncanny about looking through someone else’s photos—the mix of familiarity and distance. I know the woman in these images as my fabulous, stern grandmother. But the girl in the photos? I don’t know her at all. In many ways, she no longer exists.

Some details are concrete; the glued photos on poster board suggest they once lived in a scrapbook of their vacation, maybe their honeymoon. But most of it is guesswork. What were they thinking? What jokes, what dreams, passed between them?

My grandmother recently moved out of her apartment and into my parents' house. We've gone through photos together before, but it’s gotten harder with time. Her move feels like a signal to keep going—to finish the archive while I still can.

Around the same time, I saw I'm Not a Robot, the short film that won the Oscar this year. It stuck with me. In the film, Lara—a music producer—keeps failing CAPTCHA tests and slowly spirals into believing she might actually be a robot. She’s told her memories aren't real, that she was programmed. It’s a brutal unraveling: if your memories are fabricated, what do you have left? What can you trust?

It made me think about digital identity—the curated lives we build online, the browsing histories we leave behind. If you lost your memory, would your digital footprint be enough to tell you who you were? Would you even believe it?

In a way, that’s what I’m asking these old photos to do: tell me who my grandparents were when they were young. But photos, like digital personas, are curated too—selected, framed, shaped.

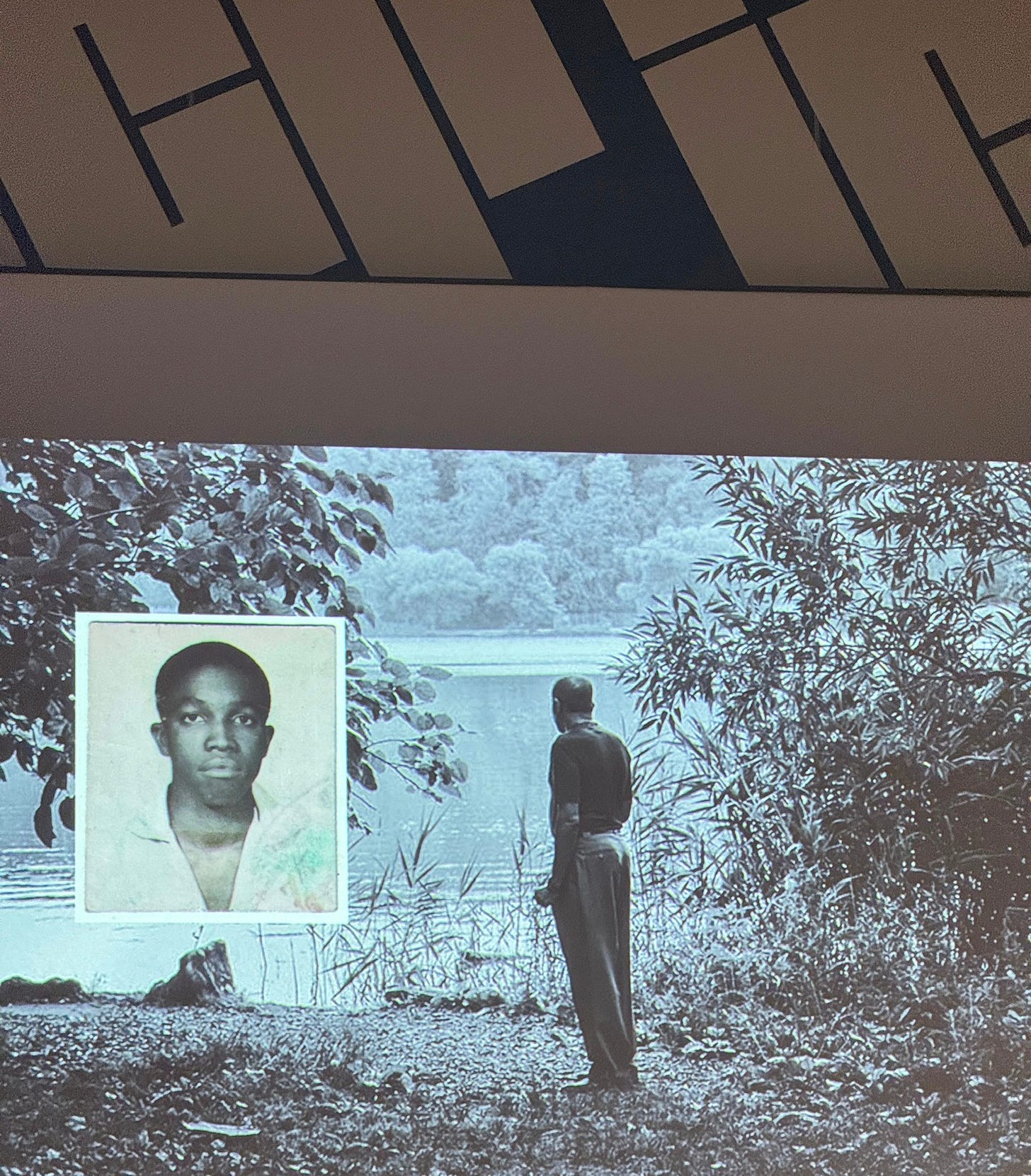

This theme echoed again in my favorite movie of the year, I'm Still Here, shot on Kodak film just like I'm Not a Robot. Set in 1970s Rio, it follows Eunice Paiva and her children as they search for the truth behind her husband’s political disappearance. The film weaves in Super 8 home footage, rich textures, and saturated colors to recreate the family's memories and the era’s atmosphere.

Photographs—and the act of documenting—become a shield against forgetting. As Alissa Wilkinson wrote in the New York Times, the film shows "how politics reshapes the domestic sphere" and reminds us to distrust anyone trying to erase the past. My family history, like countless others, is scarred by fascist upheaval. And as fascism creeps into more corners of American life, the act of remembering feels not just vital, but urgent.

Director Walter Salles said he believes “cinema reconstructs memory.” With I'm Still Here, he made sure nobody could forget.

And maybe, in my own way, I’m trying to do the same—with old snapshots, with family stories half-remembered, with a bright blue trunk that holds more questions than answers.

I’ve realized I’m not alone in this search. Others are also sifting through absence, asking images to do the impossible: to remember for us. In March, I attended the Naomi Rosenblum ICP Talks Photographer Lecture featuring Keisha Scarville in conversation with Carla Williams. Both are brilliant, prolific artists, but I was especially moved by Scarville’s archival projects, Mama’s Clothes and Passports, which explore her parents’ legacies through photography. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading this Vice article on her work. I was equally captivated by Williams’ archive of self-portraits—but saving that for a separate piece I’m working on about self-representation.

Their conversation lingered with me. They spoke of photography not just as image-making, but as a form of conjuring—of memory, of absence, of identity. Scarville described the camera as a collaborator, a participant in intimate acts of remembrance. Photography, in this frame, becomes a way of materializing what is no longer there: a loved one’s clothing, an old passport photo, a home that now only exists in recollection.

They emphasized that archives aren’t just institutional—they’re personal, emotional, and sensory. They live in attics and trunks, in clothing and gesture, in maternal lines and domestic spaces. They asked: What is the archive of me? What latent traces exist in everyday scenes? It made me think of my own attempts to make sense of my family’s past—not through orderly documents, but through fragments. Photos without captions. Objects without stories. The blue trunk in my parents’ house.

In many ways, Scarville’s work mirrors what I’ve been trying to do—grasping at memory, working with absence, and asking images to tell stories they were never meant to hold alone.

The talk also raised powerful questions about whose histories are preserved and whose are erased. For those of us descended from people shaped by migration, loss, or political violence, archival work can feel like resistance. It is a refusal to forget.

Have you ever gone through an old family archive? What did you learn—or feel—you were missing?

Thank you for reading, it means so much to me! See more of my work on Instagram, TikTok, and my website.

Want to chat? Email @ isabellecbrauer@gmail.com.